I love static websites. I have been using and enjoying various static website generators for almost three years now (like this website) and I wouldn’t want to go back to using more complex systems. But, while I’m comfortable writing my Markdown files in a text editer most non-technical content editors aren’t. They’d rather want a nice, web-based CMS.

Why can’t we have both – a static site generator that makes web developers happy and a web-based CMS for content editors?

In this article I would like to share my ideas how such a Static CMS could be designed and evaluate some existing tools in this area. First, let’s have a look at why having static websites is such a great thing.

Static Websites

In the old days, the web would basically be a bunch of HTML files on servers. Whenever someone would visit a website, a server would just send the requested HTML file over the wire. Today, we still receive HTML files from the servers but there is much more going on behind the scenes.

The majority of the web is now powered by database-driven websites. Databases are great for online editing and collaboration. But it also means that every time a website is accessed, the server has to get the data from the database and run it through the template engine until it can be served. This is a process that uses server memory and processing power (=money), slows down the website and introduces vulnerability. But most of all it creates complexity for developers and removes the joy of creating websites.

For most sites this complexity of regenerating the page on each request is completely unnecessary. After all, most websites only change when the content editor or the designer make a change. So, let’s go back to static, but it’s a different static than we had in the early days. With static site generators we can create almost any website of any size we want. And it makes the web fun again.

- Speed. The website is pre-generated HTML and ready to be served. That’s as fast as it can possibly be.

- Reliable and Scalable. Because there is no database the website can easily be served from multiple servers all around the world through content delivery networks. If one server goes down, traffic just goes somewhere else.

- Secure. Malware is a major issue for database-driven websites. No database, no php or server scripts means there is no way to inject malware in static websites.

- Maintainable. No server maintenance or server updates are needed.

- Cost. It’s very cheap to host and scale a static website.

- Simple and Fun. The simplicity of static websites fit in my brain and I feel I know what’s going on. It’s a joy for a developer to work with the fundamental elements of the web.

The Content

The most valuable part of a website usually is its content. I want my content to be in a format that can be used in various contexts. The content should stay readable even years from now and should be easy to convert to other formats.

Databases make me nervous. They are very complex systems that store my precious data in some format I don’t really understand. If some day the database stops working I might have a lot of trouble getting my data out of the system. Things change quickly and I don’t want to depend on some strange database export tool to migrate my data to the next system.

Text-based file formats have been gaining a lot of popularity, Markdown probably being the most prominent. Most static site generators support Markdown (I’m also writing this post in Markdown). I love it and it makes data simple again. It’s also very easy to create backups or version the data so that we can revert any changes.

Complex Content

Markdownify everything? I believe we need just a little bit more. Most static generators use a YAML front-matter in every file for meta-data like title, date, and author followed by the Markdown content. For more complex content this might still not be enough because we might need multiple content sections instead of just one per file.

Instead of using YAML only for the meta-data, we could use it also for the content. This allows us to define multiple content sections. While we’re at it I would strongly suggest to use TOML as an alternative to YAML.

Here is an example of how such a TOML file could look like. It is a product page for a book. In it you will see three markdown sections: book_description, product_details, and customer_reviews.

example-book.toml

title = "Go Programming By Example" date = "2015-03-15" book_description = """ Go, commonly referred to as golang, is a programming language initially developed at Google in 2007. This book helps you to get started with Go programming. The following is highlight topics in this book: * Development Environment * Go Programming Language * And more... """ product_details = """ ## E-Book * File Size: 4752 KB ## Print * Print Length: 136 pages """ customer_reviews = """ ## Go is awesome So far I like this book, and Go is just a wonderful language as it's very powerful, very fast, with a clean and simple language structure. I just wish I had more time to devote to Go... """

Every page would have such a TOML file. The static site generator takes the TOML files, runs them through the template engine and creates the website.

The CMS

Although possible, editing the TOML files in a normal text editor isn’t an option. We need a file-based CMS that shows nice forms where a content editor can make the changes. Instead of saving to a database, the CMS should save the content back to the text files.

We need to give the CMS some information about the structure of our data. This will allow it to display the correct form elements and possibly also some helper texts for content editors.

Let’s call this information about our data content types. It could also be defined in TOML. Here is a possible content type description of the book example I described above:

content-types.toml

[book] name = "Book" [[book.fields]] name = "title" label = "Title" required = true type = "text" [[book.fields]] name = "date" label = "Date" required = true type = "datetime" [[book.fields]] name = "product_description" label = "Product Description" type = "markdown" [[book.fields]] name = "product_details" label = "Product Details" type = "markdown" [[book.fields]] name = "customer_reviews" label = "Customer Reviews" type = "markdown"

Components and Workflow

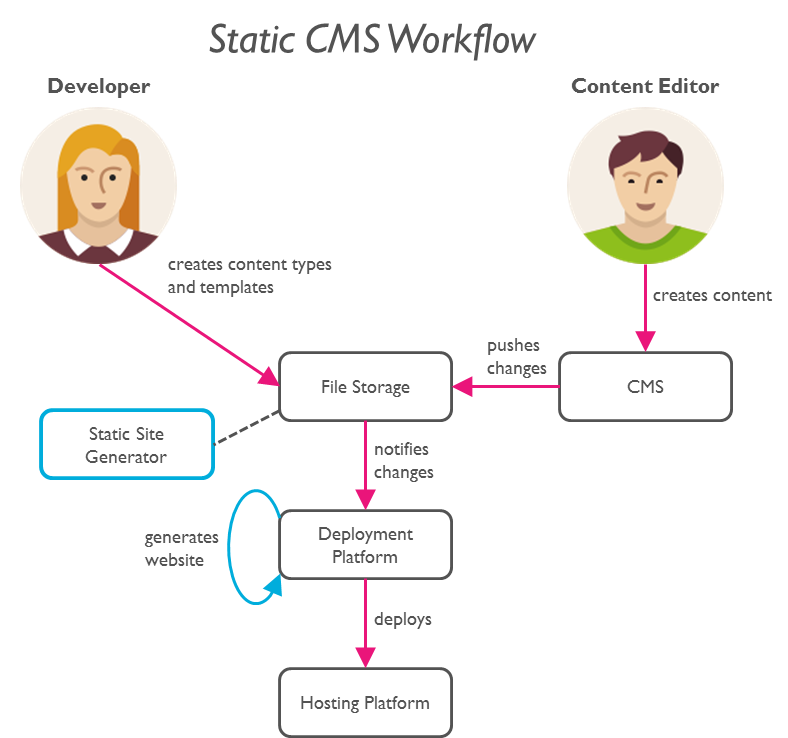

For such a Static CMS system we need five main components:

- Static Site Generator

- File Storage

- Web-Based CMS

- Deployment Platform

- Hosting Platform

Each component has a very specific task and can be grasped by the developer’s brain. The beauty of this setup is that each component is independent and can be replaced or reimplemented quite easily.

Here is the basic workflow:

Tools

There is one platform I would like to point out that provides an all-in-one solution for what I described above (except it’s not file-based). It’s called Webhook. If you haven’t seen it I recommend you check it out! I really like Webhook but in my opinion they integrate too much which leads to problems: There are so many parts that it is difficult to understand what it actually does. And I can’t (easily) exchange individual components. For example, I would love to use their web-based CMS but I would rather want to use another static generator than the one that is built in. And I also might not want to host my site on their infrastructure.

In the following I will present tools for each individual component. This is highly opinionated and most of those components may be replaced by other tools (as they likely will over time, anyways).

Static Site Generator

There is a nice list of Static Site Generators, ranked by GitHub stars.

My current favorite is Hugo. It is very easy to install (which isn’t the case with most static generators), it is very fast, has a nice templating language, supports TOML, and is written in Go.

Hugo has (almost) everything we need. I only have a few wishes that are mostly already on the Hugo Roadmap.

My Wishlist for Hugo

Allow content with non-MD extensions: The setup for complex content as described above is already possible with Hugo. But, the .md extension doesn’t really make sense if the content file only contains TOML. When issue #147 will be fixed, Non-MD files will be accepted in the content folder. We would need to make sure that the .toml files would also be processed like .md files.

Assets in the content directory: I’m desperately waiting for Issue #147 to be fixed. This would allow us to place content like images next to the MD/TOML file. I would love to have a subfolder for each page that bundles all assets for a page together! This would greatly simplify things for the CMS.

Dynamic image resizing: Ideally, the content editor would not need to worry about the image sizes but would just upload it to the content folder. Hugo would then pick up the image and resize it, based on the size defined in the template. We would need to figure out a good place for the resized images to be stored so that they don’t need to be recreated every time.

File Storage

The obvious choice for storing the files is GitHub. It is a nice tool for developers to work with and provides the versioning we need.

Web-Based CMS

The CMS is currently the biggest missing piece in our setup.

Although, an interactive web based editor is is already being discussed and is on the Hugo Roadmap, I don’t know if it is such a good idea to include this in Hugo. I think it would be better to keep the CMS and website generation separate.

There are some File-Based CMS systems but none of them are complete:

- prose.io: This is the closest to what we would need. It is missing a way of reading

TOMLconfig files and displaying a corresponding form with fields. It has something similar forYAML, but it’s too basic. - Kirby: Nice. They store the media files directly in the page folder. It has a way to define content types called Blueprints. They use a custom file format for content - I’d rather use

TOMLfor now, which is well defined and has good parsers. - Statamic: Similar to Kirby. Also provides a way to define the content types in so called Fieldsets .

- PicoCMS: Open Source but missing a lot of features (and documentation!).

- Grav: It says it is a CMS, but it doesn’t have a CMS interface. That means you have to edit the Markdown files directly. But it has an interesting feature called modular pages that lets you build a complex page from mutliple markdown files.

- Automad: An interesting way to show a GUI for file-based CMS.

Deployment Platform

Whenever something changes in either the content or the templates (on GitHub), the deployment platform must regenerate the website and deploy it on the hosting server. This is already well supported and there is even a tutorial about Hugo deployments with Wercker.

Hosting Platform

An easy and cheap solution would be to use GitHub Pages as hosting platform. How this can be done is already described in the Hugo/Wercker tutorial mentioned above.

If more features are needed I would use a platform like DivShot that has spezialized hosting for static websites. Another option is Netlify which is a combination of deployment and hosting.

Summary

I tried to show how the best aspects of static site generators and file-based CMS could be combined to create a Static CMS:

- All content is stored in

TOMLfiles that have a well-defined structure. It is in simple text files that can be versioned and provides easy backup and migration posibilities. - The structure (content types) are also defined as

TOML. The CMS picks up the content types and shows a nice form where the content editor can write the content.

→ the content editor is happy :-) - The develper works with his favorite static site generator (Hugo, for example) and sets up templates, themes and the content types.

→ the developer is happy :-) - Whenever the content editor or developer commits a change (to GitHub), the site is automatically rebuilt. The served website is static with all its benefits (speed, security, reliability, etc.).

→ everybody is happy :-)